They were here last year for our Calgary Stampede, they looked great in their cowboy gear…

Hope they come back soon.

They were here last year for our Calgary Stampede, they looked great in their cowboy gear…

Hope they come back soon.

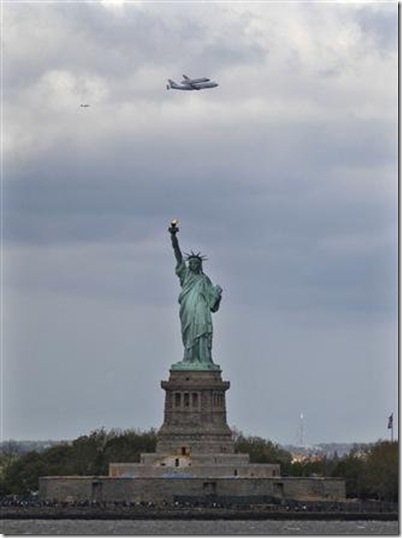

The pair left Dulles International Airport early yesterday & flew over the New York skyline before landing at the John F. Kennedy International Airport.

The pair left Dulles International Airport early yesterday & flew over the New York skyline before landing at the John F. Kennedy International Airport.

Below is a gorgeous Georgian church in England that has been renovated into a home…

The only thing a little weird are the headstones on the lawn… I would not be having family BBQ’s out there for sure…

This is the entrance, I am thinking a little bit of colour pulled from the stained glass windows would have been amazing in this hallway…

The living room, a much larger area rug to anchor the living area is all this needs…

Not sure where the kitchen is located in the floor plan but this is nice…

The dining area is between the living room and the can be curtained off master bedroom, check out the small strings of lights above… having dinner in this room must be magical…prime rib anyone ?

The master bedroom, I am so loving the use of the giant candle sticks, I think I would add a few more…

An amazing staircase

Loving the painted stone

This looks like a cosy place to sleep

To have a bath in this room must be wonderful, I would have candles going in front of the stained glass windows.

Hope you enjoyed this church to home post, could you live in an old church ? I would love to at least have an opportunity to design the interior of one for sure…

I was on line looking for ideas in bedrooms… I have 5 different bedrooms to design for a clients home for this Monday afternoon (with the rest of the house) I will not be getting much sleep this weekend!

I thought I would share this one with your from the House Beautiful website… loving the use of drapery’s over the windows

click here to see the whole post

Busy Busy day… got to go…

Have a good day everyone…

I have been blogging for a while now, time for a give away… I have been waiting for something special to be my first give away, this “domino, quick fixes” fits the bill…

just 3 things to do…

1.) Follow my blog

2.) Subscribe to my blog

3.) Leave a comment with your email address.

I will be emailing the winner for their address, so do not forget to mention it…

I will be pulling from the list of names on Saturday, May 19th…

Best of luck to everyone!

I will start with the story of Father Frank Browne

The Father Browne SJ Photographic Collection contains the most important collection of Titanic photographs taken during the liner’s voyage from Southampton to Cobh (Queenstown] in Ireland.

Frank Browne’s mother died whilst he was young and his father when in his teens. His uncle Robert Browne who was Bishop of Cloyne acted as guardian to Frank and his siblings, four of whom were to enter religious life. By the time Frank was completing his secondary education he had decided to become a Jesuit. Immediately before entering the Order, Uncle Robert sent him on a Grand Tour of Europe and most significantly bought him a camera to record his trip. This visionary act was to reveal a natural aesthetic ability and fostered an interest in photography that was to reach fruition when Frank became the most outstanding Irish photographer of the first half of the Twentieth Century.

The Bishop had another surprise up his sleeve, when in early 1912 he presented Frank with a first class ticket for the Maiden Voyage of the Titanic to bring him as far as Cobh.

So it was that on the morning of the 12th.April 1912 he arrived at Waterloo Station in London to catch the Titanic Special. He immediately started taking photographs, first recording the train journey and then life aboard the Titanic on the initial section of the voyage. Having made friends with a wealthy American family he was offered a ticket for the remaining part of the journey and no doubt excitedly telegraphed a request for permission to go on to New York, to which he received the terse response “Get Off That Ship------Provincial!” That telegram not only saved Frank’s life but also meant that this unique record of the voyage was saved for posterity and guaranteed overnight fame for Frank Browne SJ.

London to Southampton

The letter from the White Star Line that accompanied Frank Browne's First Class ticket. It was sent on 3rd April 1912.

The scene confronting Frank Browne on arrival at Waterloo Station to board the “Titanic Special” for Southampton. Browne captures a quiet platform setting with the subtle inference of wealth amongst the 1st.Class passengers, all well dressed with the men wearing top hats. The London fog obscures the more distant features, thus concentrating attention on passengers and train.

Having stowed his baggage Browne felt free to mingle amongst his fellow passengers, all seemingly preferring chatting on the platform to getting into their carriage. William Waldorf Astor on left with an umbrella appears to have assumed his usual photographic pose whilst the others are quite unconcerned. One man in the centre of the picture is loading his camera, a large Kodak “Autographic”. Perhaps he was encouraged to take pictures by Browne's enthusiastic activity..

This carefully constructed image summarises the train journey to Southampton. The components combine to create a perfectly balanced image, atmospheric elements enhance the concept of depth and the adjoining shiny tracks draw the eye forward to the steaming locomotive as it crosses the viaduct, leaving London behind. This scene could only be captured at one specific instant and Browne, leaning out of the carriage window seized the moment.

Browne took no pictures on arrival at Southampton, presumably luggage transfer had to be organised; however whilst boarding the “Titanic” by the first class gangway he paused to capture the dockside scene with the giant wall of Titanic's steel dwarfing the people on the ground. The second class gangway closes the view. Others on the quayside are boarding at a lower level, presumably the unfortunate third class passengers who were to find no possibility of escape when disaster struck.

Once aboard Frank Browne went to the Purser's office to register his arrival. There he was welcomed by Mr McElroy and given his copy of the deck plan.

In addition to the deck plan Frank Browne was given this postcard as a souvenir.

Frank Browne took two pictures in his stateroom between Southampton and Cherbourg. Lacking a wide angle lens he first photographed his richly decorated dressing table.

In this second picture of his stateroom a ghostly image of the photographer can be seen in the mirror. Close inspection of the dressing table mirror reveals something of his suite of rooms which consisted of bedroom, sitting room and bathroom. A small detail of his sitting room with a view out of what was either the window or open door can be seen and curiously a very clear detail of his clerical collar.

As the “Titanic” departed from the quayside, relatives and sightseers waved goodbye.

She had a Hazardous Start

Once he had photographed the dockside, Browne began making his way toward the bow of the vessel, he photographed three other liners tied up alongside each other, the tug “Neptune” in the corner of the picture is making its way forward to help turn the Titanic as she moves off.

On arrival at the bow end of “A” deck he photographed the tugs “Hector” and “Neptune” as they manoeuvred the “Titanic” around. This image is carefully constructed to convey a sense of activity on the “Titanic”, no doubt enlivened by the fact that no ship of this size had been so manoeuvred before; the power employed by the tugs is emphasised by the smoke belching from “Neptune's” funnel.

Excitement quickly turned to dismay when the “Titanic's” giant propellers went into action; such was the flow of water that the current pulled the adjoining “New York” so fiercely that her moorings snapped (Browne described the snapping of six cables as sounding like pistol shots) and she was drawn into the path of the “Titanic”. An early disaster was narrowly averted by quick action on the part of the tug skippers who used their powerful vessels to push the two ships apart.

This picture shows two tugs pushing the “Titanic” clear of the “New York”, at the same time the tug in the background is moving in to reposition the “New York”.

"Here we see a tug repositioning the “New York” following the near collision."

This postcard picture, purchased later, captures something of the atmosphere at Southampton as the great ship departed.

Heading towards the English Channel Titanic passed one of the giant forts constructed to defend the port.

This image combines human interest with a contrast of technologies: photographed as the “Titanic”, the world's most sophisticated ship slows to permit the pilot to transfer to the sail powered pilot boat. The round object on the horizon is one of the Portsmouth defensive forts. Ironically this like so many of the pictures features the lifeboats that were to prove so inadequate.

At sea

Whilst the “Titanic” was making way past Portsmouth Frank Browne captured this poignant image of a lone ship's officer walking along “A” deck with his back to camera.

Second class passengers exploring the deck.

A sailor stands on duty underneath the bridge, whilst some of the passengers take a last view of Portsmouth. The boy to the right is Jack Odell who with his family disembarked at Queenstown, one of the men in the background is Major Archibald Butt, military aide to President William Howard Taft.

Inside the Gymnasium Mr.TW McCawley the physical educator poses at a rowing machine and Mr.William Parr, electrician who was travelling first class, is seated on some form of exercising machine, hold still for the duration of a time exposure . Both men were lost.

The card given to Frank Browne by Mr Mc Cawley

Browne photographed this couple as they took an early morning stroll along “A” deck before the deck chairs were set out.

This man standing on the boat deck close to the gymnasium is believed to be Jacques Futrelle the American short story writer who was lost with the ship.

This must be one of the best known pictures taken on the “Titanic”. The six year old Robert Douglas Spedden whipping his spinning top, watched by his father Frederic, has attracted the attention of other passengers.

This is the only picture taken of the Titanic’s radio room. Perhaps one should say pictures as this is a double exposure and was destined for the bin until hastily recovered. In it we see Harold Bride at work in what was the most advanced radio room in the world.

Second class passengers are shown here gazing down at the photographer on “A” deck. The aft end of the boat deck was available to second class as a promenade area. The morning air must have been chilly, most people are wearing warm coats.

The Luncheon menu prepared for the 14th. April, the last to be served on the “Titanic”.

This photograph of the first class dining room at mealtime must have presented the greatest challenge of the series, although well lit for dining purposes it could not be considered so from a photographic point of view. In fact it is very successful, conveying as it does something of the scale and grandeur of the room enlivened by the diners at their tables.

This interior view of the Titanic's First Class reading and writing room conveys some idea of the opulence of the liner's grand interiors.

Arrival

Having enjoyed a good night's rest Browne was up early next morning in order to catch this glorious sunrise as the ship passed close to Cornwall, en route between Cherbourg and Queenstown, at about 6-45am. On the 11th. April 1912.

This image of a sinuous wake was described by Browne as “A winding pathway o'er the waters “. He then explains that “on the way from: Lands End to Queenstown the “Titanic” steered a very irregular course in order to test her compasses.”

The bow wave which is central to this picture has been positioned to form a balanced near abstract image in conjunction with the horizon and ship's side. A touch of realism is introduced in the distance by emergency lifeboat No.1 hanging out over the side.

This picture was probably taken from the shore at a position close to Roche's Point Lighthouse and presents a clear impression of the spectacle of the “Titanic” entering the bay.

Titanic photographed off Roche's Point

Obviously Frank Browne could not photograph the arrival of the “Titanic” at Queenstown so subsequently he acquired photographs of the event from photographer friends. In his album he describes this picture as “Dropping Anchor at Queenstown. 12-15 pm. Apr. 11th.”. In fact the ship is still moving and preparing to drop anchor. The picture is drop anchor. The picture is attributed to Mr. McLean and was taken from the tender “America”.

The Tender Ireland towing two rowing boats. Help appreciated by the oarsmen.

Mail being taken aboard from the Tender America.

The Tenders Ireland and America brought passengers, baggage and mail to the Liners anchored in the outer harbour.

A view of the White Star Terminal at Cobh with tenders in waiting.

Close up view of the Tender Ireland from her sister vessel America.

This stern view of the Titanic was taken as the ship came came to a stop having dropped anchor. The head and shoulders of a seaman can be seen above the rear funnel, which was in fact a ventilation shaft, he climbed up to get a grandstand view of Titanic's arrival at Cobh.

This picture of a Tender alongside the Titanic was given to Frank Browne by his friend Tom Barker.

This, one of the most emotive images of the series captures the anchor as it emerges from the water for the last time. The heavy plates protecting the bow are impressive but proved to be sadly inadequate when ripped apart by the ice.

Once on the tender Browne took the opportunity to take pictures of the Titanic and of the liner's departure. This image with a flock of gulls wheeling around “Titanic's” bow conveys something of the impressive scale of the ship, further emphasised by the rowing boat in the foreground.

Browne's last photograph of the “Titanic”, taken as she gathers speed on the fateful final leg of her journey. In the foreground the men in the boat are taking advantage of a tow from the tender “America” which carried press and photographers to the scene.

Eight people disembarked at Queenstown, all but one were first class passengers, the other was a stoker from the engine room and was probably transferring to another liner. The party were brought ashore on the tender “Ireland” captained by Mr. McVeigh. In the centre are L to R. Stanley May and his brother RW May, the author. Both these gentlemen wrote to Frank Browne following the tragedy.

Another family group photographed by Browne on the tender was of .the Odells. The boy wearing a school cap is Jack Odell, his mother is in the centre whilst Captain McVeigh is to be seen to their right.

The tenders disembarked their passengers at the White Star Wharf. In this crowded picture we see people waiting to be taken aboard a liner, the upper gallery of the building appears to have been reserved for first class passengers who are not concerned with the crush below.

Cobh(Queenstown) in mourning with flags at half staff outside both the Cunard and White Star offices. 19th April 1912

*****

Frank Browne put together an album of his Titanic photographs into which he wrote captions and an account of his experiences at the start of the voyage.

Name: also included photographs of other ships at Cobh including those of the Titanic's sister ship Olympic, thus filling in features that were never photographed on the Titanic. He amplified this coverage with pictures of onshore activities related to the maritime activities at Cobh. This is Page three of his album.

Titanic Album page eight

Titanic Album page twelve

Titanic Album page forty-four.

Titanic Album page forty-five.

Titanic Album page fifty-one.

Titanic Album page fifty-two

Titanic Album page fifty-three.

Titanic Album page fifty-four

Titanic Album page fifty-seven

The cover of the Daily Sketch, Thursday 18th. April 1912. This newspaper made extensive use of Frank Browne's pictures, bringing him overnight fame.

Inside double page spread of the Daily Sketch, Thursday 18th April 1912, featuring many of Frank Browne's pictures.

The White Star Line wrote to Frank Browne regarding his illustrated lectures asking him to refrain from mention of the loss of the Titanic with the strong suggestion that they would like the incident to be forgotten...

We we will not forget the Titanic and all the lives lost….

Trivia

On Board Titanic

· The cost of a first-class ticket on Titanic to New York was $2,500, approximately $57,200 today. The most expensive rooms were more than $103,000 in today's currency.

· A third-class ticket at Titanic cost $40, which is approximately $900 in today's currency. Up to 10 people resided in third-class rooms. The rooms were divided by male and female often times splitting families.

· First-class passengers had the luxury of paying for their leisure while on board: a ticket to the swimming pool cost 25¢, while a ticket for the squash court (as well as the services of a professional player) cost 50¢.

· Sixty chefs and chefs' assistants worked in the Titanic's five kitchens. They ranged from soup and roast cooks to pastry chefs and vegetable cooks. There was a kosher cook, too, to prepare the meals for the Jewish passengers.

· Titanic had its own newspaper, the Atlantic Daily Bulletin, prepared aboard the ship. In addition to news articles and advertisements, it contained a daily menu, the latest stock prices, horse-racing results, and society gossip.

· There were only two bathtubs for the more than 700 third-class passengers aboard the Ship.

· The forward part of the boat deck was promenade space for first-class passengers and the rear part for second-class passengers. People from these classes thus had the best chance of getting into a lifeboat simply because they could get to them quickly and easily.

Disaster Strikes

· Even if all 20 lifeboats had been filled to capacity, there would only have been room in them for 1,178 people.

· At first most of the passengers did not believe Titanic was really sinking, hence the low number of 19 aboard the first lifeboat, even though it could carry 65.

· Titanic was one of the first ships in distress to send out an "SOS" signal; the radio officer used "SOS" after using the traditional code of "CQD" followed by the ship's call letters.

· Dorothy Gibson, a 28-year-old silent screen actress, was the resident movie star for Titanic. She would later star in Saved from the Titanic, a movie made one month after the disaster. Her costume was the dress she wore on the night of the sinking.

· Tennis player R. Norris Williams and his father, Charles D., felt it was too cold to remain out on deck as the ship went down, so they went into the gym to ride the exercise bikes.

· At the time of Titanic's destruction, the temperature of the water was only 28°F (-2°C). Most of those struggling in the water in their life jackets would have succumbed to hypothermia, while others may have had heart attacks.

The Aftermath

· Initial headlines of the Titanic disaster claimed all passengers survived and the ship was being towed to land.

· The White Star Line was not blamed for Titanic's sinking because the Board of Trade feared that this would result in lawsuits that would hurt the line's profits, damage the reputation of British shipping, and cause thousands of customers to switch to German or French liners.

· No skeletons remain at the wreck site. Any bodies carried to the seabed with the wreck were eaten by fish and crustaceans.

· In the 1898 novel Futility, 14 years before the sinking of Titanic, Morgan Robertson penned a fictitious tale about a ship named Titan, which collide with an iceberg. Some of the uncanny similarities between the book and the Titanic disaster include the month (April), the length of the ship (Titanic 882.5 feet, Titan 800 feet), and the number of passengers on board (Titanic 2,200; Titan 2000).

Titanic FAQ

Why was Titanic built?

Although Titanic is best known for carrying the rich and famous between Europe and the United States, the Ship actually had several purposes:

1. To carry British and US mail--hence the full name of the ship is Royal Mail Ship (RMS) Titanic.

2. To carry general cargo and frozen meat since at that time Europe could not produce enough livestock to meet its own needs.

3. To carry first-class passengers in great luxury, second-class passengers in great comfort and third-class passengers with great economy.

4. To fly the flag of Great Britain and uphold national honour. Even though Titanic was ultimately owned by American business interests, the Ship was built in a British yard, operated by British subjects, manned by British crews and perceived by the public as a British ship.

How large was Titanic? How many crew were onboard?

Titanic was 882 feet 9 inches long, 92 feet 6 inches in breadth. Titanic weighed 46,329 tons or 103,575,360 pounds.

There were 1,316 passengers on board: 325 in first-class, 285 in second, and 706 in third-class. At the time of the sinking, the Ship's crew consisted of 885 men and women divided between three departments: Deck Department, 66; Engine Department, 325; Victualling (Passenger Care) Department, 431.

Not included in this list are the eight members of the Ship's band who were technically from another company and traveled under second-class tickets.

Who built Titanic?

Titanic was constructed by the shipbuilding firm of Harland & Wolff at their Queen's Island Works in Belfast, Ireland. Edward Harland acquired the yard in 1859. A few years later, G. W. Wolff was taken into the partnership and in 1862 the name changed to Harland and Wolff. By the time of Titanic's construction, both these men had either died or gone into retirement, and the company placed under the management of Lord Pirrie.

Why was Titanic said to be unsinkable and where did the story come from?

Titanic was described in the popular press as "practically unsinkable." This was not unusual – for decades, ships had watertight compartments to limit flooding in case of an accident, and the press used this phrase as a matter of routine for many years.

After Titanic sank, the story of her loss was turned into a modern fable and the original description "practically unsinkable" became just "unsinkable" in order to sharpen the moral of the story. No educated person in 1912 believed that Titanic was truly unsinkable, but it was difficult to imagine an accident severe enough to send her to the bottom.

Was Titanic warned about the icebergs in the area?

Yes, the first ice warning came in by wireless at 9:00 the morning of the collision from the Cunard Liner Caronia. As the day progressed, several additional wireless warnings came in from ships in the region warning of ice ahead.

How long did it take Titanic to sink?

Titanic struck the iceberg at 11.40 p.m. on Sunday, April 14, 1912 and sank 2 hours, 40 minutes later at 2.20 a.m. the next day.

Where is the wreck site of Titanic?

Titanic's wreck site is located 963 miles northeast of New York and 453 miles southeast of the Newfoundland coastline. Titanic lies 2.5 miles beneath the ocean surface, where the pressure is 6,000 pounds per square inch.

What ships came to Titanic's rescue and what ships did not?

Titanic's distress call was received by several ships the night of the disaster including the Carpathia, Mount Temple, Virginian, Baltic, Caronia, Prinz Fredrich Wilhelm, Frankfurt and the Titanic's sister ship the Olympic. Initially, several of these ships altered course towards the collision site, but when it became apparent that Carpathia alone would make it to the scene of the accident in reasonable time, they resumed their previous courses. One ship, the Leyland Line's Californian was only a few miles distant from the Titanic. The Californian had stopped for the night in pack ice because her Captain felt it too dangerous to proceed through the ice field in the dark. Although fitted with wireless, the Californian's operator had turned in for the night and missed the distress call. To this day, there is considerable controversy as to whether the Californian's deck officers were negligent in not making a more aggressive investigation into rockets and lights seen in the distance.

Why didn't Titanic carry enough lifeboats?

Titanic's lifeboat capacity was governed by the British Board of Trade's rules, which were drafted in 1894. By 1912, these lifeboat regulations were badly out of date. The Titanic was four times larger than the largest legal classification considered under these rules and by law was not required to carry more than sixteen lifeboats, regardless of the actual number of people onboard. When she left Southampton, Titanic actually carried more than the law required: sixteen lifeboats and four additional collapsible boats. The shipping industry was aware that the lifeboat regulations were going to be changed soon and Titanic's deck space and davits were designed for the anticipated "boats for all" policy, but until the law actually changed, White Star was not going to install them. The decision seems difficult to understand today, but in 1912, the attitude towards accident prevention was much different. At the turn of the century, ship owners were reluctant to exceed the legal minimum because lifeboats took up most of the space on first- and second-class decks. Boats were expensive to purchase, maintain, and affected a ship's stability. Finally, in the years before the Titanic Disaster, it was felt that the very presence of large numbers of lifeboats suggested that somehow the vessel was unsafe. Oddly, the same reluctance showed up as late as the 1950s for automobile seatbelts. Car makers at that time were also reluctant to install seatbelts because the belts seemed to imply there was something unsafe about the car.

Were third-class passengers deliberately kept below decks?

Both the British and American inquiries found that there was no evidence to suggest that third-class passengers were deliberately kept below decks, although it is true that third-class passengers did not make their way to the Boat Deck until very late in the sinking. A reasonable explanation is that the Ship’s officers were overwhelmed by the disaster and simply overlooked sending specific orders to evacuate third-class. White Star had formulated no emergency plans for this type of accident and the Ship’s officers were fully preoccupied with the crisis of damage control and the launch of lifeboats. In an attempt to provide for an orderly evacuation, third-class stewards held passengers below waiting for orders that nobody thought to give.

Were only women and children allowed in the lifeboats?

Traditionally, first seats in lifeboats are given to women and children, with men filling up the late leaving lifeboats; however, given Titanic’s lifeboat shortage, this tradition meant that the casualty list was more heavily male. On the port side of Titanic, the lifeboat launchings were supervised by Officer Lightoller, who took this order literally, preventing any men except the boat crews from embarking. Early in the sinking, women were naturally reluctant to abandon a ship that did not seem at all to be in trouble, and as a result, many of these boats were sent away only partially full. On the starboard side, Officer Murdoch interpreted the order to mean "women and children first on deck" – and only after all the seats had been offered to women, could any men on hand, who wished to evacuate, do so.

How many survivors are alive today?

The last living survivor, Millvina Dean, recently passed away on May 31, 2009 was the oldest survivor of Titanic at age 97.

Can Titanic be raised?

Sadly, even if the technology existed to raise it from the seabed, the wreck is far too fragile to withstand lifting and transportation.

Who discovered the wreck?

The location of the wreck was discovered by Dr. Robert Ballard and Jean Louis Michel in a joint U.S./ French expedition on September 1, 1985 at 1:05 a.m.

Recovery

Expeditions to recover Titanic artifacts have been a collaborative effort between RMS Titanic, Inc.; The French Oceanographic Institute; and the Moscow-based P.P. Shirshov Institute of Oceanology. These expeditions have been conducted at the Titanic's wreck site, located 963 miles northeast of New York and 453 miles southeast of the Newfoundland coastline, during the summers of 1987, 1993, 1994, 1996, 1998, 2000 and 2004.

Nautile and MIR submersibles are used for the recovery in Expeditions 1987, 1993, 1994, 1996 and 1998; these machines are equipped with mechanical arms capable of scooping, grasping, and recovering the artifacts, which are then either collected in sampling baskets, or placed in lifting baskets. The crew compartment of each submersible accommodates three people – a pilot, a co-pilot, and an observer – who each have a one-foot-thick plastic porthole between themselves and the depths. Both submersibles have the capabilities of operating and deploying a Remote-Controlled Vehicle on a 110-foot tether, which is then flown inside the wreck to record images.

In the 2004 Expedition, the Remora 6000 Remote Operated Vehicle (ROV) was used for the recovery of objects. This ROV was controlled from the surface via ROV pilots.

It takes over two and a half hours to reach the Titanic wreck site. Each dive lasts about twelve to fifteen hours with an additional two hours to ascend to the surface.

Each recovered artifact must then undergo conservation following carefully designed processes to remove rust and salt deposits from each object.

Once an artifact leaves the water and is exposed to the air, it must undergo an immediate stabilization process to prevent further deterioration. When recovered from salt water, artifacts are cleaned with a soft brush and placed in foam-lined tubs of fresh water. Once received at the conservation laboratory, contaminating surface salts are removed from each artifact. After a period of six months to two years, artifacts can be conserved using treatments that are compatible with each artifact's construction materials.

For instance, metal objects are placed in a desalination bath and undergo the first steps of electrolysis, a process that removes negative ions and salt from the artifact. Electrolysis is now being used to remove salts from paper, leather, and wood as well. These materials also receive treatments of chemical agents and fungicides that remove rust and fungus from them.

Artifacts made of paper are first freeze-dried to remove water and are then cleaned with specialized vacuums and hand tools to remove dirt and debris. Leather artifacts are soaked or injected with a water-soluble wax which replaces voids previously filled by water and debris.

Artifacts are displayed in specially designed cases where temperature, relative humidity and light levels can be controlled, protecting the artifacts from these three agents of deterioration. The artifacts displayed have been conserved and are continuously monitored and maintained so that they can be shown in the Exhibition as well as preserved for the future.

The wreck of the Titanic remains on the seabed, gradually disintegrating at a depth of 12,415 feet (3,784 m). Since its rediscovery in 1985, thousands of artefacts have been recovered from the sea bed and put on display at museums around the world. Titanic has become one of the most famous ships in history, her memory kept alive by numerous books, films, exhibits and memorials.

Victoria -- The Royal B.C. Museum in Victoria hosted an exhibit of artifacts recovered from the Titanic.

The exhibit opened April 14, 2007 exactly 95 years after the ship struck an iceberg and sank in the Atlantic Ocean in 1912.The exhibit in Victoria was the first time I saw the artifacts from the Titanic…

This is the last exhibition that I visited last year here in Calgary,

this is a fun picture that was taken of us @ the exhibit…

there were things in the second exhibition that we had not seen before.

*********************

Then there was a very special piece that I could not forget, I went back to look at it a few times while being at the exhibit that day… I could not forget it after leaving either… I kept thinking I had seen something like it before… I was sure that I had been admiring a bracelet like it at Tiffany’s…

This is the one from Titanic…it is the most amazing piece…imagine they found this beautiful piece on the bottom of the ocean.

This is the one from Tiffany’s, they have many different designs like it, I was wanting one before I found my little sterling silver lock…

Now a few weeks later I was at Calgary’s Heritage Park (a very nice place to visit if your ever in Calgary Alberta) roaming though their antique shop and found a small antique sterling silver lock…I had to have it, I just had to… I found when I got home I had my mothers old silver bracelet from the 1960’s so I took them both to my local fine jewellery shop added a new lobster claw clasp and had them put the two together… check it out !!!

When I wear it I feel like I am wearing one of the most timeless pieces in the world…

Timeline

April 2nd, 1912, 8:00 p.m.

The crew of Titanic participates in sea trials before leaving Belfast, where the Ship was built, for Southampton.

April 10th, 1912, 6:00 a.m.

Just after sunrise the first members of the crew began to board Titanic. All of the officers except Captain Smith had already spent the night on board. Captain Smith arrived later that morning around 7:30.

April 10th, 1912, 12:00 p.m.

Titanic starts maiden voyage, leaving Southampton and ventures to Cherbourg, France, and Queenstown, Ireland (this is the official sailing date for the Ship).

April 11th, 1912, 1:30 p.m.

Titanic raises anchor for the last time and leaves Queenstown.

April 14th, 1912, Morning

Lifeboat drills were neglected after church services, although the crew has to complete the procedure.

April 14th, 1912, 10:55 p.m.

Californian, completely surrounded by ice, stops for the evening and warns the Titanic of the impending danger.

April 14th, 1912, 11:40 p.m.

Frederick Fleet sights an iceberg.

· First Officer Murdoch gives the "hard a-starboard" order while having the engines stopped and reversed; activates lever that closes watertight doors.

· The Ship, traveling at approximately 20 knots (26 mph), turned slightly to the left, avoiding a head-on collision. Below the water the iceberg punctures the hull.

· Five, possibly six of the Titanic's watertight compartments flood.

April 15th, 1912, 12:15 a.m.

Captain Smith assesses the damage. He orders his telegraph operators to send the distress signal, "CDQ," after estimating the ship will remain afloat for two hours.

He gives the order to uncover the lifeboats and evacuate the women and children.

April 15th, 1912, 12:45 a.m.

First lifeboat leaves the Ship with only 19 aboard, although it could carry 65.

April 15th, 1912, 2:05 a.m.

Titanic's bow begins sinking as the last of the lifeboats are lowered into the water. An estimated 1,500 people were left stranded on the sinking boat

April 15th, 1912, 2:20 a.m.

Titanic sinks.

The Strauses

Isidor Straus, 67, and his wife Ida, 63, almost always travelled together; in fact, they were rarely apart during their married life and wrote each other daily during periods of separation.

The son of German immigrants who had settled in Georgia, Isidor met Ida when he and his brother moved to New York City following the Civil War. Isidor arrived penniless in New York because he had paid every one of his debts before he left Talbotton, Georgia, even though standard practice at the time was not to honour the suddenly worthless Confederate scrip. Soon, though, Isidor and his brother Nathan became involved in the firm of R.H. Macy & Co., and eventually acquired it. Isidor also served as a New York congressman from 1895-97.

The Strauses—now wealthy philanthropists who generously supported dozens of causes in New York— had travelled to Europe early in 1912, crossing the Atlantic on the German liner Amerika. It was their custom to travel on German steamers whenever possible, but on their return trip to America they decided to travel on the maiden voyage of Titanic.

Isidor, Ida, and the Night of the Titanic Sinking

On the night of the disaster, as the call to board the lifeboats went out, Isidor escorted Ida to Lifeboat 8 and prepared to say goodbye to her. Ida, however, refused to enter the small boat, saying, “We have lived together for many years. Where you go, I go.” Several other first- class passengers tried to convince Ida to board but she could not be swayed. Instead, she sent her newly employed maid, Ellen Bird, in her place, after first wrapping her in a fur as protection against the cold. The Strauses were last seen seated side by side on Titanic’s Boat Deck.

The Strauses were not far from a member of their family on the night of their deaths. Their eldest son, Jesse Isidor, the US Ambassador to France, was travelling back to Paris on the Amerika, which had sent Titanic an ice warning earlier that day. Jesse Isidor had also sent his parents a personal telegram, mentioning the ice he had seen.

Isidor’s body was recovered by the Mackay-Bennett. A funeral service for Isidor was delayed for a few days in the hopes that Ida’s body might too be recovered, allowing the two who had lived and died together to also share a funeral—but Ida’s body was never found. Several days later, over twenty thousand people gathered at Carnegie Hall in New York City for a memorial service in the Strauses honour.

A few of the Survivors…..

Mr & Mrs Albert Dick, of Calgary, Alberta Canada

I live in Calgary, Alberta very close to their home, they mentioned him this evening on our local news. I will have to drive by the home this weekend and check it out, I just never new where it was…

Name: Mr Albert Adrian Dick

Born: Thursday 29th July 1880

Age: 31 years

Last Residence: in Calgary Alberta Canada

1st Class passenger

First Embarked: Southampton on Wednesday 10th April 1912

Ticket No. 17474 , £57

Cabin No.: B20

Rescued (boat 3)

Disembarked Carpathia: New York City on Thursday 18th April 1912

Died: Tuesday 2nd June 1970

Cause of Death: Cause Not Disclosed

Albert Adrian Dick

(Courtesy: Alan Hustak, Canada)

Mr Albert Adrian "Bert" Dick, 31, was born in Winnipeg, Manitoba, 29 July 1880, but was raised in Alberta when it was still a Canadian territory. He and a brother started a sawmill in Ponoka, and by 1904 they were so successful they began selling real-estate and commercial properties in Calgary. By the time Bert was 24 the Dick brothers had built the Hotel Alexandra on 9th Ave. S.E., and the Dick business block on 8th St. S.E., which still stand.

On the day Titanic was launched, 31 May 1911, he married Vera Gillespie, who was born in Calgary in 1894. She was still a socially gauche teenager, so Bert took his wife on a belated honeymoon to the Holy Land, and to educate her, they made the Grand Tour of Europe. They had returned through London to pick up solid, serviceable reproduction antiques for their new Tudor-style home at 2111-7th Ave. in Calgary's affluent Mount Royal District.

2111-7th Ave, Mount Royal, Calgary

(Courtesy: Alan Hustak, Canada)

They booked passage home on Titanic as first class passengers. They boarded the ship at Southampton and occupied Cabin B-20 (ticket number 17474, £57).

Aboard ship, one of the younger stewards, a man by the name of Jones, took a shine to Vera, and much to Bert's annoyance, Vera flirted with him. They were also befriended by Thomas Andrews, and on the last night of the voyage the Dicks shared his table at dinner. Vera Dick was to say afterwards that she would always remember the stars that night. "Even in Canada where we have clear nights I have never seen such a clear sky or stars so bright."

The Dicks were getting ready for bed when the ship hit the iceberg, and felt nothing. They were made aware of the accident when the same steward who had taken a shine to Vera knocked on their door and told them to dress. "We would have slept through the whole thing if the steward hadn't knocked on our door shortly after midnight and told us to put on our lifejackets," Mrs Dick told a Calgary newspaper. Both were escorted to lifeboat 3 by Thomas Andrews who saw them off. According to Bert, and his wife were locked in a farewell embrace, when he was pushed into the lifeboat with her. As the boat jerked towards the water, the Dicks wondered whether it might not capsize and whether they might not be safer had they not left the ship.

When they returned to Calgary, Bert was ostracised because he had survived. His name was tarnished by gossip that he had dressed as a woman to get off the ship. His hotel business suffered, so he sold it and continued to make money in real estate. Vera studied music at the Royal Conservatory of Music in Toronto, and was well known as a vocalist in Calgary. They built an elaborate brick staircase in front of their house that local gossip said was patterned after the Titanic's grand staircase, however it does not look anything like it. They had one daughter, Gilda.

The "Titanic Staircase"

(Courtesy: Alan Hustak, Canada)

Albert Adrian Dick died in Calgary, Alberta on 2 June 1970. His wife died in Banff, Alta. on 7 October 1973. Both are buried in Calgary's Union cemetery. Lot 4, Block 1, Section L.

(Courtesy: Alan Hustak, Canada)

Travelling Companions (on same ticket) ![clip_image001[1] clip_image001[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhAvCuFT_Awlib5qRURR2ZP9XtkA_5Gy0CFa56T7DzWusaZy5vBnRa6cA6Pc7D1FRfzCDp7SzRxKrDBq8o9-XDxgm26qk-5WA5bNeWylP3RYequ7MlOn4UDIS-8hkY_IwoGXDQ3gPoQN0P2/?imgmax=800)

Sir Cosmo and Lady Duff Gordon

![clip_image001[4] clip_image001[4]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhZdv36ns2UphP9tuESAUYekvYRZXBML1I3s5FarDwn_qaDburiSfvKqBwh_t_mdXtynOmEPyxOWM9YZ_6lgOHZoXHYdAsXh32IIqUcW0dlJFGtmxbILqX9WKFKcJ2IECoDZXesd9lkOz4x/?imgmax=800)

Sir Cosmos Duff Gordon, was a Scotsman. His ancestor James Duff, was British consul in Cadiz during the Penisular War. Naturally, he was into every enterprise, the Sherry trade being big.

The Gordons both boarded a lifeboat early in the sinking, taking their personal servants with them. Their lifeboat departed the ship with just 12 or so people aboard, although it could have held 30 or so more.

After watching the ship dive beneath the water, amidst the screams of the 1,500 people calling for help that they were ignoring, the tactless Lucy commented to her secretary, "There is your beautiful nightdress gone." Two sailors commented "It's all right for you, you can get more clothes, but we have lost everything." Cosmo then gave the men a "fiver" each ($360.00 today) to help them out, a gesture that would cost him a lot more later when he was accused of bribing the crew to let him escape the liner and then row away without helping any of the victims in the water.

Upon their return to London society, the couple were shunned in some circles, and constantly gossiped about by London society.

Unable to have children, their marriage slowly disintegrated and they drifted apart until 1931, when Cosmo died. Soon after his death, Lucy's business went bankrupt, and she later died in 1935.

Edith Brown Haisman

Mrs. Edith Brown Haisman, the oldest survivor of the Titanic, died at the age of 100 on January 20, 1997. She was 15 years old when placed in Lifeboat #13 as the Titanic sank. Her father, Thomas Brown, a glass of brandy in hand, waved from the deck saying "I will see you in New York."

In 1993 she described her ordeal:

"I was in Lifeboat #13. I always remembered that. My father was waving to us and talking to a clergyman, the Rev. Carter."

"The Titanic went in the ice and I heard three bangs. Before we hit, there had been terrific vibrations from the engines during the night as the ship was really racing over the sea."

"As the lifeboat pulled away we heard cries from people left on the Titanic and in the water and explosions in the ship. There were lots of bodies floating ... We were in the lifeboat nine hours."

"I kept looking in the water for my father and when we reached New York we went to the hospitals to see if he had been picked up."

Edith married the late Frederick Haisman in South Africa. They had 10 children and more than 30 grandchildren.

Anna Turja

"I can never understand why God would have spared a poor Finnish girl when all those rich people drowned." ~~ Anna Turja Lundi, Titanic survivor.

She was 18 years old when she boarded the Titanic in Southampton, England, as a Third-Class (Steerage) passenger on her way to America. To her the ship was a floating city. The Main-Deck, with all its shops and attractions, was bigger than the main street in her home town. The atmosphere in Third-Class was quite lively with a lot of talking, singing, and fellowship. Anna shared a room with two other young ladies.

The others of the group continued up to a higher deck, but she remained on what turned out to be the Boat-Deck. She thought it was too cold to go up further, and she was intrigued by the music being played by Titanic's Band. She also remembers seeing the lights of another ship (the "Mystery Ship") from the deck.

Anna didn’t fully understand what was going on because she did not know the language. Eventually a sailor physically threw her into a lifeboat. Lifeboat #15 was fully loaded when it was launched. They immediately rowed away from the ship, fearing that they would get sucked down with it when it went under. She heard loud explosions as the lights went out.

They were in the lifeboats for eight hours. They had to burn any scraps of paper or anything they had that would burn so that the lifeboats could see each other and stay together. Her most haunting memory was that of the screams and cries of dying people in the water.

Anna remembered the people aboard the Carpathia were wonderful. They gave up their blankets and coats, anything that could help. Anna kept looking for her roommates, but she never saw either of them again.

She was greeted by a crowd in Ashtabula, as she was somewhat of a celebrity by this time. She soon met her future husband, Emil Lundi, John’s brother. They fell in love and got married. She never did go to work for her brother-in-law.

Anna's name turned up on the lost passengers list. Her family in Finland didn’t know that she was alive until 5 or 6 weeks later when they received a letter from her.

In May of 1953, she was a special guest when the movie "Titanic" came to the theatre in Ashtabula. It was the first movie she had ever seen in her life. It was so realistic, all she could say was, "If they were close enough to film it, why didn’t they help?"

Over the years she was interviewed regularly by the local newspapers when the anniversary of the sinking came around, but she turned down appearances on "I’ve Got a Secret" and "The Ed Sullivan Show", partly because of her physical condition and the language problem. She also refused many times to join in any lawsuits over the loss. She had her life, and felt that was compensation enough.

Every year on the April anniversary she would sit her seven children down to tell them the story again. The phrase she would always close with, and repeated throughout her life was, "I can never understand why God would have spared a poor Finnish girl when all those rich people drowned."

Anna Sophia Turja Lundi died in Long Beach, California, in 1982 at the age of 89.

Margaret Devaney

At the age of 19, Margaret Devaney boarded that 'unsinkable' ship, the Titanic, to take her to the Promised land. Instead, she found Brooklyn and Jersey City. But as is often the case, extraordinary events make heroes out of peasants and unfortunately, tragedy makes for good story telling.

Margaret Devaney O'Neill fled her small village in County Sligo in 1912 to escape famine, poverty, and the English, just as thousands of others had done, to seek out a new life in the New World. She carried with her a suitcase, some odds and ends, and the clothes she had on at the time.

Margaret was below decks in Third-Class [Steerage] peeling potatoes on April 14th, 1912 when she decided that she needed some fresh air. With coat in hand she headed up the many flights of stairs to the Main-Deck (Boat-Deck). As she was nearing the top of the final flight she felt a tiny bump that interrupted the constant motion she had grown accustomed to over the last four days. It was, of course, the collision with the iceberg that would cause the Titanic to sink. Unfortunately 2,230 passengers and crew tried to fit into 20 lifeboats. Margaret was literally thrown into Collapsible Lifeboat #C when she was trying to go back to Steerage to find her three traveling companions who boarded with her. She didn't know they were already doomed: Sealed behind bulkheads that were closed to try to prevent the ship from sinking.

On the lifeboat with about 50 other terrified souls it appeared that she would at least survive the sinking, but the officer in charge could not detach the lifeboat from the quickly sinking Titanic. The story goes that Margaret gave him the little knife that she had been using earlier to peel potatoes and with it he was able to cut the boat loose.

After her lifeboat was picked up by the Carpathia the officer returned the knife to Margaret and gave her the ensign, which is the plaque that is attached to the side of each lifeboat bearing the White Star Line symbol. He gave her the ensign to thank her for the knife, but he also knew that people would begin tearing apart the lifeboats as souvenirs and he wanted to make sure that she had something to tell her grandchildren about.

Margaret Devaney died in 1975, but her story lives on.

The Becker Family

Ruth Becker Blanchard (1899-1990):

Richard Becker:

Richard Becker was Ruth's younger brother and was two years old at the time of the disaster. Richard became a singer and in later life a social welfare worker. Widowed twice, he passed away in 1975.

Nellie Becker:

Nellie Becker was the children's mother. She was married to a missionary stationed in India and her three children were sailing to America for treatment of an illness Richard had contracted in India. Once in America, she and her three children settled in Benton Harbour, Michigan, until her husband's arrival from India the following year. It was apparent to him and the children that her personality had changed since the disaster. She was far more emotional and was given to emotional outbursts. Until her death in 1961, she was never able to discuss the Titanic disaster without dissolving into tears.

Marion Becker:

Marion contracted tuberculosis at a young age and died in Glendale, California in 1944.

Olaus Abelseth

Returning to the South Dakota farm he had first homesteaded in 1908, he raised cattle and sheep for the next 30 years before retiring in North Dakota where he died in 1980.

Colonel Archibald Gracie IV

A member of the wealthy Gracie family of New York state, one of Gracie's ancestors had built Gracie Mansion which became the official residence of the mayor of New York City in 1942. Gracie was a graduate of St. Paul's Academy in Concord, New Hampshire and of West Point Military Academy. Later becoming a colonel in the Seventh Regiment, United States Army, Gracie was independently wealthy, active in the real estate business and an amateur military historian.

His father served with the Confederate forces as militia captain of the Washington Light Infantry. In 1862, he was promoted to brigadier general and fought through the Battle of Chickamauga, one of the bloodiest battles of the American Civil War. On December 2nd, 1864, General Gracie was killed while observing Union Army movements at the siege of Petersburg, Virginia.

Gracie took return passage on the Titanic, boarding at Cherbourg. He had spent much time with Mr. Isidor Straus who had regaled him with tales of his adventures during the Civil War. He loaned Mr Straus a copy of his new book, "The Truth About Chickamauga".

On Sunday morning following breakfast, Gracie attended Church service in the First-Class Dining Room, where the hymn was No. 418 of the Hymnal, "O God our help in ages past". He then spent some time with Mr. and Mrs. Isidor Straus and they returned the book he had loaned them.

Sunday night, after dinner, Gracie and his table companions Clinch Smith and Edward Kent, adjourned to the Palm Court where they enjoyed coffee as they listened to the Titanic's band. After circulating and socializing for a while, Gracie retired early to his cabin, C-51. After about three hours sleep, he was awakened by a jolt. He noted the time as 11.45 p.m., then opened the cabin door and looked out. He saw no one and heard no commotion. He could hear steam escaping and there was no sound of machinery running. Realizing that something was wrong, Gracie removed his nightwear and got fully dressed. Wearing a Norfolk coat, he left his cabin and made his way the Boat-Deck.

It was a cold, starlit night with no moon. There was no sign of ice or other ships. He jumped over the barrier dividing First and Second-Class and roamed the entire Boat-Deck. He saw a middle aged couple strolling along arm-in-arm but there was no sign of any officers or any reason for concern. Returning to the A-Deck companionway he encountered Mr. Bruce Ismay - the Managing Director of the White Star Line - with a crew member, they seemed preoccupied and did not notice him.

At the foot of the stairs there were a number of men passengers who had also been disturbed by the jolt, and he learned that the ship had collided with an iceberg. They noticed a tilt in the deck realized that the situation was worsening. The men returned to their staterooms where Gracie hastily packed all his possessions into three large travelling bags ready to transfer to another ship. After putting on a long Newmarket overcoat and returning to the deck, Gracie found that everyone was putting on the life preservers.

Gracie spent most of the remaining time assisting women into the lifeboats. Mrs. Straus almost entered Lifeboat #8, but turned back and rejoined her husband. She had made up her mind: "We have lived together for many years. Where you go, I go." Gracie tried to persuade her, but she refused. Mr. and Mrs. Straus went and sat together on a pair of deck chairs.

Gracie continued to assist in the loading of women and children into Lifeboat #4. One of the ladies Gracie lifted into the boat was the pregnant teenage wife of Colonel John Jacob Astor IV.

At around 2.00 a.m. all of the Titanic's rockets had been fired and all the lifeboats had been lowered except for the four collapsible Englhardt boats with canvas sides.

Collapsible Lifeboat D was lifted, righted and hooked to the tackles where Lifeboat #2 had been. The crew then formed a ring around the lifeboat and allowed only women to pass through. The boat could hold 47, but after 15 women had been loaded, no more women could be found. Men were now allowed to take the vacant seats. This was when Gracie found Mrs. Brown ("The Unsinkable Molly Brown") and Miss Evans were still on board, so he escorted them to the lifeboat. When Gracie arrived with the female passengers, all the men immediately stepped out and made way for them. Thinking there was only room for one more lady, Edith turned to Mrs. Brown and told her, "You go first. You have children waiting at home." Mrs. Brown was helped in and the boat left the Titanic at 2.05 a.m. under Quartermaster Bright. Edith Evans would never find a space in any of the lifeboats and died in the sinking.

As the collapsible was lowered to the ocean, two men were seen to jump into it from the rapidly flooding A-Deck. Ironically these two men were Gracie's friends, Woolner and Bjrnstrm-Steffansson, who had found themselves alone near the open forward end of A-deck. Just above them Collapsible Lifeboat D was slowly descending towards the sea, and as the water rushed up the deck towards them they got onto the railing and leapt into the boat, Bjrnstrm-Steffansson landing in a heap at the bow. Woolner's landing was similarly undignified but they were safe.

Gracie was still working on the Collapsibles when the Titanic's bridge dipped under at 2.15 a.m. As the Titanic foundered, Gracie stayed with the crowd. As the water rushed towards them, Gracie jumped with the wave, caught hold of the bottom rung of the ladder to the roof of the officers mess and pulled himself up. As the ship sank, the resulting undertow pulled Gracie deep into icy waters, he kicked himself free far below the surface and, with the aid of his life preserver, swam clear. Clinging to a floating wooden crate, Gracie was able to swim over to the overturned Collapsible Lifeboat B and, with a little help managed to climb onto it. When Gracie first got to the boat there were about a dozen people on it. All told some thirty men and women managed to climb on the partially submerged boat during the next few minutes.

Just after 3.30 a.m. the survivors heard the sound of a cannon being fired, and as dawn broke around 4 a.m. the Carpathia came into sight. The men on Collapsible Lifeboat B were now desperately trying to stay afloat. The Carpathia was 4 miles away, picking up survivors from the other lifeboats. About 400 yards away, Lifeboats #4, #10, #12 and Collapsible D were strung together in a line. By 8.15 a.m. all Lifeboats were in but for Lifeboat #12. At 8.30 a.m., Lifeboat #12 made fast and Gracie was able step onto the Carpathia's gangway.

Colonel Gracie wrote an account of the tragedy that was published as "The Truth About The Titanic" in 1913. Gracie never finished proofing the manuscript as he died on December 4th, 1912 at his ancestral home in New York, N.Y., having never fully recovered from the trauma of that night. Many survivors were at the graveside for his burial, together with members of his regiment.

Archibald Gracie was the third survivor of Titanic to die, being preceded in death by Maria Nackid on July 30th, 1912 and Eugenie Baclini on August 30th, 1912. Colonel Gracie's final surviving child,

Edith Temple Gracie Adams, died childless in 1918, about a year after her marriage.

" ... there arose to the sky the most horrible sounds ever heard by mortal man except by those of us who survived this terrible tragedy. The agonising cries of death from over a thousand throats, the wails and groans of the suffering ... none of us will ever forget to our dying day." ~Quote by Colonel Archibald Gracie IV

The Countess of Rothes

Soon, when Miss Edwards was around her twenties, she met Norman Evelyn Leslie (nineteenth Earl of Rothes), and their relationship became a wedding on the twenty-first of June, 1900. As soon as Miss Edwards said, "I do", she became the Countess of Rothes. She had two sons with his lordship, who (at the time of the Titanic) were eleven and two-and-a-half.

Lady Rothes was heading to America on the Titanic, so that she could join her husband, who wished to settle down for the rest of his life as a fruit-farmer, and spend a summer vacation in Pasadena, California.

When the Titanic sank, her Ladyship boarded Lifeboat #8 with her cousin and her maid. There, she took the tiller, and Able Seaman Tom Jones said, "She had a lot to say, so I put her to steering the boat". He admired the Countess of Rothes greatly, and later represented her with a plaque from the lifeboat, representing the number.

On board the Carpathia, her Ladyship earned the title of "the plucky little Countess", by the crew, for she helped the sick in Steerage and helped make clothes for the babies. A stewardess said, "You have made yourself famous by rowing the boats", and her Ladyship replied, "I hope not; I have done nothing".

At the Ritz Carlton, her Ladyship joined her husband, Lord Rothes, and they left for California. The Countess's husband, Earl Rothes, died in 1927, and she soon met Colonel Claude MacFie that same year and became Mrs. Noel MacFie in December. She lived with the colonel in Sussex and died there on September 21st, 1956.

J. Bruce Ismay

He was first an apprentice in Liverpool, then an agent in New York and in 1891, upon returning from America with his wife Florence, became a partner in the firm. Although at first resistant to IMM's (International Mercantile & Marine) bid to buy White Star, Ismay agreed to J.P. Morgan's attractive offer in December, 1902. A year later he accepted the position of IMM president.

His wife and four surviving children did not accompany him on the Titanic. Ismay made his escape from the wreck on lifeboat Collapsible C, for which he spent the rest of his life marked as a selfish coward, especially in America.

Bruce Ismay retired as planned from the International Mercantile Marine in June 1913, but the position of managing director of the White Star Line that he had hoped to retain was denied him.

Surviving the Titanic disaster had made him far too unpopular with the public. He spent his remaining years alternating between his homes in London and Ireland. Because Ismay had never had many close friends, and subsequently had few business contacts, it was mistakenly easy to assume that he had become a recluse. He did enjoy being kept informed of shipping news but those around him were forbidden to speak of the Titanic.

Joseph Bruce Ismay died in 1937, at the age of seventy-three

Masabumi Hosono

Masabumi Hosono, the only Japanese passenger on the Titanic, stood on the Boat-Deck, torn between the fear of shame and the instinct for survival. Then the 42-year-old Japanese bureaucrat found himself in the right place at the right moment. There were two spots open in Lifeboat #10. Hosono hesitated, but when he saw a man next to him jump in, he swallowed his fear and followed.

Hosono's decision saved his life - yet it brought him decades of shame in Japan. He was branded a coward, fired from his job and spent the rest of his days embittered. He died in 1938, a broken man.

The Laroche Family

Born in Cap Haitian, Haiti, Mr. Laroche, 26, had been living in France since 1901. There he studied engineering and met Juliette Lafargue, whom he married in 1908. The couple had two daughters, Simonne and Louise, who was born prematurely on July 2, 1910 and suffered many subsequent medical problems.

The move was planned for 1913. In March 1912, however, Juliette discovered that she was pregnant, so she and Joseph decided to leave for Haiti before her pregnancy became too far advanced for travel. Joseph's mother in Haiti bought them steamship tickets on the La France as a welcome present, but the line's strict policy regarding children caused them to transfer their booking to the Titanic's second class.

On April 10 the Laroche family took the train from Paris to Cherbourg in order to board the brand-new liner later that evening. There was no mention of a black family aboard the Titanic by any of the press or survivors accounts. This is unusual for the time when prejudice was very existent.

Mr. Laroche, the only black passenger on the Titanic, did not survive the sinking of the Titanic. His wife and two daughters were saved in lifeboat #10.

On August 8, 1973, Simonne, who never married, died at the age of 64.

Mother Juliette, died At age 91 on January 10, 1980. On her grave a plaque is engraved: Juliette Laroche 1889-1980, wife of Joseph Laroche, lost at sea on RMS Titanic, April 15th 1912.

Louise Laroche passed away quietly in Paris, France on January 28, 1998 at the age of 87. She was 21 months old when rescued from the Titanic.

Michel & Edmond Navratil

Wishing to stop his mother-in-law's interference in his marriage, Michel Navratil (a French tailor) kidnapped his two children Michael M. (age 3) and Edmond Roger (age 2) from his estranged wife Marcelle, and sailed aboard Titanic.

The divorce proceedings were in process and the Easter Sunday, April 7th was Michel's day to visit the children. In a well thought out plan he picked up the boys at his mother-in-laws and took them to England to board the Titanic. He had a revolver in his pocket in case of interference.

Marcelle's mother had been caring for the boys while she worked as a seamstress to supplement the family income. The mother-in-law constantly undermined Michel's standing in the family. At the end of the Easter weekend Marcelle went to pick the boys up from their father but they were no where to be found. She never dreamt that her name would be a household word on two continents.

"Hoffman" isolated himself from the other passengers during the crossing. He rarely let the boys out of his site not trusting anyone. Only at one point when he wanted to participate in a card game, he did. He let a Swiss woman by the name of Bertha Lehmann who spoke only French and German, but not English, look after the children.

Mr. Navratil remained behind after placing his sons in Collapsible D. When the Titanic sank, Michel Navratil was aged 32 years. His last residence was in Nice, France. He had boarded the Titanic as a 2nd Class passenger at Southampton on Wednesday April 10, 1912, Ticket No. 230080, Cabin No. F2. His body was recovered by the Mackay-Bennett (No. 15) and was buried at the Baron De Hirsch Jewish Cemetery, Halifax Nova Scotia Canada on Wednesday May 15, 1912.

Aboard the Carpathia, Edmond and Michel (unable to speak English) were dubbed "the Orphans of the Titanic" when they turned out to be the only children who remained unclaimed by an adult. First Class survivor, Miss Margaret Hays agreed to care for the boys at her New York home (304 West 83rd Street) until family members could be contacted. They were assumed to be Hoffmans.

In later life Edmond worked as interior decorator and then became an architect and builder. He was married. During World War II he fought with the French Army, was captured and made a prisoner-of-war. He managed to escape from the camp in which he was held, but his health had suffered and he died in the 1954 at the age of 43.

Michel Marcel became a scholar and teacher of philosophy and received his doctorate in 1952. He had two sons (a doctor of Urology and a German translator) and two daughters (a psychoanalyst and a music critic).

The boys mother, Marcelle Navratil, died in 1974.

Michel Navratil lived in France until his death on January 30, 2001. He was the last male Titanic survivor.

Mr. Michel Navratil was buried in the Jewish "Baron de Hirsch Cemetery" in Halifax. The officials offered to move his body to the Catholic section after the error was discovered but his wife was quite happy to leave the body where it was resting. No member of the family had ever visited Mr. Navratil's grave until Michel Marcel did - then 88 years old. Following Jewish tradition many visitors had honoured his memory by leaving stones on his marker to signify their having stopped to pay their respects.

Edmund (left) and Michael (right)

Marian Thayer & her Son, Jack

From the Philadelphia Inquirer, Saturday, April 15, 1944:

Obit For MRS. JOHN B. THAYER

When the Titanic sunk on April 14, 1912, off Newfoundland after striking an iceberg, her husband, 2nd vice president and director of the Pennsylvania Railroad, was carried to his death, but Mrs. Thayer and her son, John B. Thayer, Jr., were rescued in a lifeboat.

Mrs. Thayer was the daughter of the late Frederick Wister Morris, and lived in Cheswold Lane, Haverford. She had been ill a year. Surviving, besides John, are another son, Frederick M., of Newtown Square, and two daughters, Mrs. H. Hoffman Dolan, of Haverford, and Mrs. H. E. Talbott, Jr., of New York. Funeral services will be held at 5 P.M. Monday at the Church of the Redeemer, Bryn Mawr.

Jack Thayer:

From his Obit, September 23, 1945, Philadelphia Inquirer ...

John B. Thayer, 3d, financial vice president of the University of Pennsylvania and a member of an old Philadelphia family, who had been reported missing since Wednesday, was found dead, his wrists and throat cut, in a parked automobile near the P.T.C. loop at 48th St. and Parkside Ave. yesterday morning.

Mr. Bell said that Mr. Thayer had been suffering from a nervous breakdown during the last two weeks. "The breakdown," Mr. Bell explained, "was due, I believe, to worrying about the death of his son, Edward C. Thayer, who was killed in the service."

The P.T.C. employees who found the body on the front seat of the car with the feet under the steering wheel are George E. Wharton, of 2036 N. 54th ST., a supervisor, and Daniel Petetti, a mechanic, of 1247 N. 54th St.

They said they first saw the automobile, a sedan, registered in the name of his wife, Mrs. Lois C. Thayer, parked adjacent to the trolley loop on the south side of Parkside Ave. at noon Thursday. When they saw the same car parked there yesterday, they investigated.

Mr. Thayer's mother, Mrs. Marian Longstreth Morris Thayer, died at her Haverford home April 14, 1944, which was the 32nd anniversary of her husband's death on the liner Titanic, which sank after striking an iceberg in the Atlantic.

Robert W. Daniel, Philadelphia Banker

I was far up on one of the top decks when I jumped. About me were others in the water. My bathrobe floated away, and it was icily cold. I struck out at once. I turned my head, and my first glance took in the people swarming on the Titanic’s deck. Hundreds were standing there helpless to ward off approaching death. I saw Captain Smith on the bridge. My eyes seemingly clung to him. The deck from which I had leapt was immersed. The water had risen slowly, and was now to the floor of the bridge. Then it was to Captain Smith’s waist. I saw him no more. He died a hero.

The bows of the ship were far beneath the surface, and to me only the four monster funnels and the two masts were now visible. It was all over in an instant. The Titanic’s stern rose completely out of the water and went up 30, 40, 60 feet into the air. Then, with her body slanting at an angle of 45 degrees, slowly the Titanic slipped out of sight."

While aboard the rescue ship Carpathia, he met fellow Titanic survivor Mrs. Lucien P. Smith, whose husband perished during the disaster. The two were married in 1914 in New York City.

Robert W. Daniel died on December 20, 1940, at the age of 56. Eloise Smith Daniel had died on May 3, 1940.

Mrs. Daniel Warner Marvin, on her honeymoon

Daniel Warner Marvin and Mary Graham Carmichael Farquarson were married on January 12, 1912. They boarded the Titanic at Southampton. Travelling as first class passengers, the couple were returning to New York City from their honeymoon in Europe. They occupied cabin D-30.

Mrs Marvin was rescued in lifeboat 10 but Daniel Marvin died in the sinking. His body, if recovered, was never identified.

On October 21, 1912, Mary gave birth to a baby girl, the posthumous daughter of Daniel Warner Marvin. She named the baby Mary Margaret Marvin.

In the spring of 1913, Mary Marvin met Horace DeCamp and fell in love. In 1916, Horace adopted Mary Margaret, the daughter from Mary's first marriage. Horace and Mary had two children of their own ... a daughter born in 1918 and a son in 1920.

Mary and Horace DeCamp (passport photo, 1921)

Horace DeCamp died in 1954 at the age of 67. Eighty year old Mary died on October 16, 1975.

Master William Rowe Richards

When the Titanic sank William Rowe Richards was aged 3 years. His last residence was in Penzance Cornwall England. He boarded the Titanic as a 2nd Class passenger at Southampton on Wednesday April 10, 1912, Ticket No. 29106. Destination: Akron, Ohio.

William Rowe Richards survived the sinking (lifeboat 4) and was picked up by the Carpathia disembarking at New York City on Thursday April 18, 1912.

He died January 9, 1988 from heart failure brought on by heart disease.

His mother, Mrs. Sidney Richards (Emily Hocking), 24, was born in Penzance, Cornwall, the daughter of confectioner and baker, William Rowe Hocking and wife Mrs Eliza Needs Hocking. She lived with her family at 38 Adelaide Street, Penzance.

Emily married Mr James Sibley Richards and moved to 'The Meadow', Newlyn. They had two sons, William Rowe Richards (named after his maternal grandfather) and George Sibley Richards and a daughter, Emily. Her husband subsequently emigrated to Akron, Ohio and she planned to join him there.

She boarded the Titanic at Southampton as a second class passenger with her two young sons under ticket number 29106, having been transferred from the Oceanic. She traveled with her mother, Mrs Elizabeth Hocking, her brother George Hocking and sister Nellie Hocking.

Emily Richards and Addie Wells had strolled the deck of the Titanic the night of the 14th, noticing how cold it was. She had just put her children to bed and was about to go to bed herself when the Titanic collided with an iceberg.

After the collision, her mother rushed into her room and shook her. Mrs Hocking said "There is surely danger, something has gone wrong." Mrs Richards and her other family members put on their slippers and outside coats and dressed the children and then went up on deck in their nightgowns. As they went up the stairs a crewmember called out that "Everyone put on life preservers." Mrs Richards returned to her cabin, as family members reassured themselves that nothing was the matter. They returned to deck and were told to pass through the dining room to a rope ladder placed against the side of the cabin that led to an upper deck. Mrs Richards, her two sons, her mother, and her sister were pushed through a window into lifeboat 4. They were told to sit in the bottom of the boat. Some of the women tried to stand after the boat pulled away, however the crewmen pushed them with their feet back into a seated position. The boat was only a short distance away from the Titanic went it went down. The people in the boat pulled seven men out of the water.

The Richards and Hockings hoped that George Hocking had been rescued by another ship, but this had not happened. After leaving the Carpathia, the Richards stayed at Blake's Star Hotel at 57 Clarkson's Street in New York City and she was reunited with her husband Sibley ("Sib") Richards who had travelled from Akron.

She ultimately returned to the UK to live. Her husband died on July 3, 1939 at the age of 51. Emily continued to live in Paul, near Penzance, Cornwall until her death on November 10, 1972. She is interred in the Paul Cemetery, Cornwall.

Berthe Leroy

At the beginning of 1910, Mrs Mahala and Mr. Walter Douglas, an American who co-founded the Quaker Oats Company, were staying in Paris. Mrs Douglas asked Berthe to join her staff and the young lady became her Travelling Companion. Berthe made the first of many trips across the Atlantic ocean along with her new employers.

In April 1912, the Douglas’s were on a trip in Europe; they wanted to buy new pieces of furniture for their Lake Minnetonka house. Mr. Douglas wanted to celebrate his 53rd birthday at home, in America, so the couple decided not to stay too long in Paris. The first liner sailing from France was the Titanic. The Douglas’s had a ticket (number PC 17761) purchased at the Parisian offices of the White Star Line. They boarded in Cherbourg, where a strange thing occurred. According to Mrs Douglas, a man who was speaking broken English told her that the Titanic was cursed, that she had better disembark in Ireland. Mrs Douglas felt uneasy and sent Berthe after the man. Berthe never could find him. Mr. Douglas laughed and told his wife that the ship was unsinkable. The Douglas’s occupied cabin number C-86, on C-Deck, and Berthe was in cabin C-138.

Berthe had vivid memories of a brilliant life on board, of evening parties, gala dinners and special meals held in honour some of the most fortunate passengers. Life was simply beautiful until the shout: Everybody on deck! rang out.

Berthe stated she heard the noise of the collision with the iceberg, which she first thought was nothing but the rumble of a storm. She was sleeping, and did not worry at first. She did not answer the order to leave ship shouted by a sailor who knocked many times at their door. She later admitted, some day in 1966, that she imagined this was a trick from a young man whom, she thought, was rather fond of her and tried to have her open her door. Much later, when she noticed that the ship was tilting forward and because the sailor was insisting at the door, she finally put a dressing gown over her night gown and hurried out of her cabin, with only one slipper on as she could not find the second one, and a lifebelt she found in a cupboard.

The corridors were almost deserted, she remembered. As they were not lighted, she found it difficult to reach the upper deck, finding her path reading the cabin numbers on the brass plaques glinting in the dark. She hoped she would meet her employers up there.

She was one of the last passengers to leave the liner on the next to the last lifeboat, #2. Because of the dark, she did not notice that Mrs Douglas was also in the same boat.

It was ten minutes after 4 a.m. Mrs Douglas was the first survivor to set foot on the rescue ship. She hysterically shouted that the Titanic had gone down with hundreds of passengers, and one crew member had to quiet her down. On the Carpathia, Berthe met Mrs Douglas, and both women were given comfort and warmth.